Civil Rights

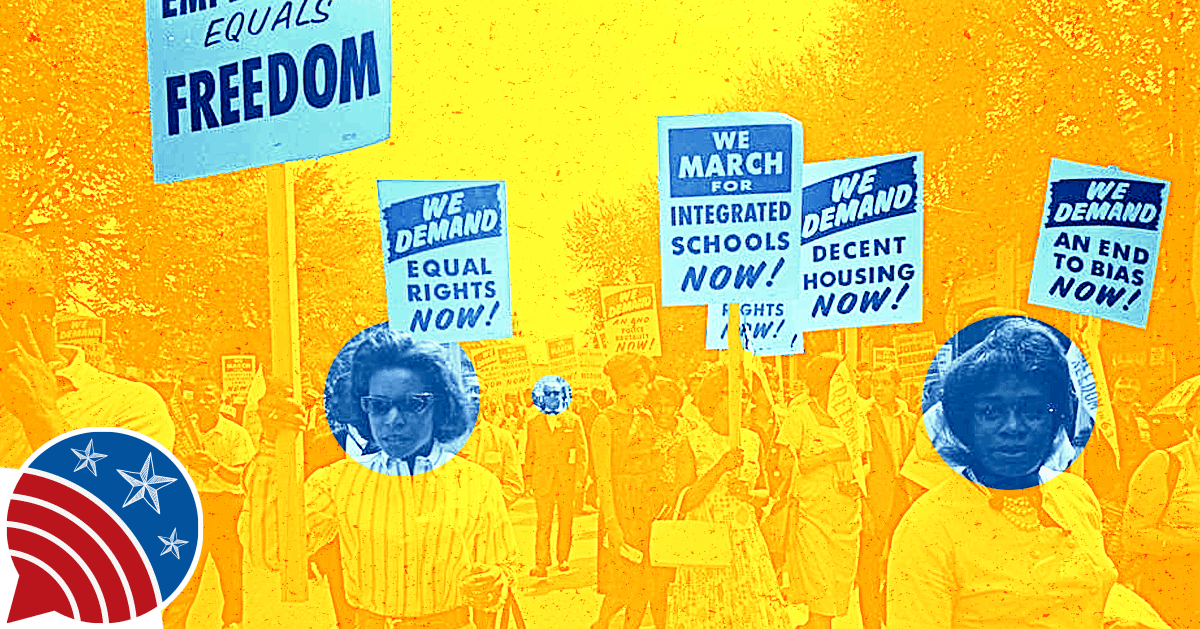

Since its founding, the Constitution has been used, challenged, and made more perfect. All of this has been done to secure civil rights for groups whose rights have not always been protected. Explore the history of civil rights in America from its founding to today. How did Reconstruction amendments, civil rights legislation, and court cases like Brown v. the Board of Education shape the evolution of American civil rights? What issues still remain today? Prepare to engage in discourse on our country’s history with civil rights and what that means today and in the future.

Podcasts & Videos

Beyond the Legacy: Civil Rights

Instructions

- Watch and listen to the 60-Second Civics video below. If you'd like, you can also read along using the script that appears below the quiz. Or you can turn on the video's subtitles and read while watching the video.

- Take the Daily Civics Quiz. If you get the question wrong, watch the video again or read the script and try again.

Episode Description

Dr. Donna Phillips: Welcome to Beyond the Legacy and Extension of the Civil Discourse An American Legacy Project. I'm Donna Phillips. Today, we go deeper into our series on civil rights in America. And we are joined again by special guest Dr. Lester Brooks, American history professor emeritus from Anna Randall, Community College. Welcome back, Dr. Brooks.

Dr. Lester Brooks: Thank you.

Dr. Donna Phillips: I'm really excited to go deeper into our topic of civil rights. And I wonder if you can start off by talking with us about how the decisions of our founders and framers shaped the challenges and battles for civil rights.

Dr. Lester Brooks: We can go straight to the Declaration of Independence because of the principles that were established in that document. Certainly, these were ideals, the revolutionary ideology. All men are created equal. Now, certainly there were flaws, but it puts us on the path to make a more perfect union. And certainly in the revolutionary period, we saw that in the Black community, there were petitions sent to provincial legislatures seeking emancipation.

Dr. Lester Brooks: And so we can find this in Massachusetts. We can find it in Connecticut seeking emancipation later. The idea of segregation will come about. But again, we can go right to the Declaration of Independence. When we talk about that revolutionary period, the Declaration of Independence and its principles sets us on a path to make a more perfect union. There was one individual at the time by the name of Lemuel Haynes, who wrote a pamphlet called Liberty Extended.

Dr. Lester Brooks: And he essentially was saying that the the Declaration of Independence should be extended to incorporate the Black community and to incorporate others. And so we get these ideas that were generated in the revolutionary period. The British offered freedom to those Blacks that would come and support the British cause. So that was one option because the Black community was seeking liberty.

Dr. Lester Brooks: They were seeking freedom. Certainly the Patriot Cause ultimately open its enlistments to Blacks as well to fight. So this idea of liberty was embedded in the Black community and freedom. And if we look at that period, those principles were crucial and they were sort of like a bedrock for people in this country. Liberty, freedom and certainly the words in the Constitution to make a more perfect union was something that people strove to bring about.

Dr. Donna Phillips: And so our country was founded very imperfectly with this goal of a more perfect union. And these principles articulated in the declaration and kind of codified by the Constitution. But they didn't apply to everyone.

Dr. Lester Brooks: Absolutely. If we look at the Declaration of Independence, certainly women weren't included. Blacks included. Native Americans weren't included. But the words themselves left an opening. And with that opening up, individuals began to seek to extend those principles to a wider audience. And that's been the struggle in this country to extend the principles of the declaration to a wider audience here in America and to incorporate all Americans.

Dr. Donna Phillips: And so if we jump forward a little bit and we look at Frederick Douglass and his invitation to speak at the Fourth of July celebration. What did he have to say about our civil rights journey?

Dr. Lester Brooks: Frederick Douglass, one of the most courageous of the abolitionists. So here, by the antebellum period, the early 1800s, we get the abolitionist movement. And Frederick Douglass was one of the key individuals there. And his speech, what to the slave is the Fourth of July celebrates that the ideas of the Declaration of Independence. And he continually talks about the Declaration of Independence and those principles.

Dr. Lester Brooks: I'd like to quote Frederick Douglass from that speech, because I think it's very timely. Douglass says this. "What have I or those I represent to do with your national independence are the great principles of the Declaration of Independence extended to us. Your high independence only reveals the immeasurable distance between us. The blessings in which you rejoice are not enjoyed in common."

Dr. Lester Brooks: "The rich inheritance of justice, liberty, profits, prosperity and independence bequeathed by your fathers is shared by you, not by me. The Fourth of July is yours, not mine." So these are powerful words from Frederick Douglass, who is recognizing the contradiction in the declaration of Independence. Yet he holds out hope. He's saying later in this speech that he still has hope for the future of the country, that things will work out.

Dr. Lester Brooks: So he, too, saw that this was a struggle, that this was an evolutionary process, and that there is this slowly chipping away at the institution of slavery, that the principles of the Declaration of Independence would in the future be extended to all. In addition to Frederick Douglass, there were others in the abolitionist movement that were fighting for civil rights.

Dr. Lester Brooks: There was a White individual by the name of William Lloyd Garrison, who also was very outspoken. And one of the words that one of the phrases of Garrison I really liked, he said, you can't. So the argument was, should slavery be abolished immediately or gradually? And there was a discussion at that time about immediate ism or gradualism. And William Lloyd Garrison, his argument was, you can't tell a woman whose house is on fire that you will gradually put out the fire.

Dr. Lester Brooks: And that really captures a very important aspect here of abolitionists and slavery. He was saying we should immediately begin to emancipate the slaves, abolish the institution of slavery. And I think his input is that he moved the the abolitionist movement along and propelled it further down the cause of immediate abolition. There were others, Sojourner Truth, also, who was protesting for abolishing the institution of slavery, as well as for extending women's rights.

Dr. Lester Brooks: So there were a number of abolitionists who were attempting to bring about the fulfillment of the principles of the Declaration of Independence. And we can't forget those individuals because they had a huge uphill climb to try and bring about the end of the institution of slavery.

Dr. Donna Phillips: And and so getting to the other side of the Civil War and then we have the Reconstruction Amendments. And how did they move the needle in terms of civil rights?

Dr. Lester Brooks: The Reconstruction era was a profound period in American history, in particular for the freedmen. The 13th Amendment abolished the institution of slavery. This is major. This is changing the status of Black Americans forever. It's abolishing the institution of slavery. Of course there is. That question was dropping the shackles? Was removing the shackles? Was that enough? Was there more?

Dr. Lester Brooks: Do you have to put flesh on this? What else is there, then? Just dropping the shackles. And so we begin to see a civil rights era. 1866. There was a Civil Rights Act, and this was the first attempt to try and put some flesh on that 13th Amendment, a Civil Rights Act. And usually we don't think about Civil Rights Act, Civil Rights Act in that period of reconstruction.

Dr. Lester Brooks: But the Civil Rights Act of 1866 essentially was saying that the freedmen would be citizens of the United States. And essentially they were trying to nullify what were called the Black codes that were popping up in the southern states that were restrictions placed on the Black community, keeping them without property and without power, without influence. So here we get a Civil Rights Act in 1866.

Dr. Lester Brooks: The 14th Amendment comes about. The 14th Amendment at the time essentially was saying that Blacks were citizens of the United States. So, again, putting more teeth to that Civil Rights Act of 1866. The 14th Amendment talks about citizenship for the freedmen. It also talks about the equal protection of the laws. And I think that phrase is going to be extremely important in the 20th century because the 14th Amendment will be used time and time again to extend the principles that were presented in the Declaration of Independence and the words of the Constitution to make a more perfect union.

Dr. Lester Brooks: The 15th Amendment. The Voting Rights Amendment. Now, it was carefully crafted at that time. Carefully worded because it left loopholes, for instance, in in crafting the wording, no one wanted women to vote in that time period. So it was crafted to continue to keep women from voting. It was also it allowed loopholes to keep Blacks from voting. So here we get the loophole tax.

Dr. Lester Brooks: If you want to vote, you have to pay. Let's say you have to pay a dollar. Well, majority of Blacks then have the overwhelming majority of Blacks didn't have a dollar, and so they would not be allowed to vote. And if I'm the White registrar, even if they have the money, I won't let them vote. Poll taxes. There were also literacy tests.

Dr. Lester Brooks: If, again, I'm the White registrar and a Black person wants to vote, I'll say, Here's a paragraph of the US Constitution. Read that paragraph for me. Now, approximately 90% of the freedmen could not read coming out of slavery. So again, the idea of a literacy test is going to exclude many in the Black population. But again, if I'm the White registrar and I do fine, one of the percentage to a Black person that can read.

Dr. Lester Brooks: Now my question will be read that paragraph and explain it to my satisfaction, which they will never be able to to do. So that was another way to keep Blacks from voting. A third method to keep Blacks from voting was the grandfather clause and extraordinary tactic. And we've seen political tricks throughout the history of politics in this country.

Dr. Lester Brooks: This is an extraordinary one where I can say to a Black person, I will let you vote. If your grandfather could vote in the election of 1860. Well, certainly no grandfather, no Black person could vote in the election of 1860. So I'm not in violation of the 15th Amendment because I'm not using race as a means of keeping that person from voting.

Dr. Lester Brooks: Because, again, the way that the 15th Amendment is crafted, it says race wins are not keeping individuals from voting based on their race. I'm saying because your grandfather couldn't vote. You're not allowed to vote. Now there will be another about another there'll be another case, a race, us versus race. I believe it is where the court will say that the 15th Amendment doesn't confer.

Dr. Lester Brooks: It just says why you can't keep people from voting. It doesn't say that you have to actually vote. So there were a lot of ways to play with that. The loophole in the 15th Amendment to keep individuals from voting. The grandfather clause will last into the 20th century. Literacy test will last into the 1960s, where in the 1960s, I might say to a person who wants to vote here, read this paragraph of the state constitution or copy this paragraph or copy the entire state constitution.

Dr. Lester Brooks: So the literacy tests are going to last into the 1960s, so that fine, it's going to last a very long time. With regard to the 15th Amendment and voting. So when we look at the reconstruction amendments, after they're called the 13th, 14th and 15th, they move the needle tremendously. They open the door. Now, certainly there were drawbacks. There were still obstacles to overcome.

Dr. Lester Brooks: For example, 1875, we get a Civil Rights Act again. Now 1866, we have one 1875, a civil Rights act essentially said that INS, hotels, theaters, accommodations should be open to Blacks. Well, there are a number of cases, such as the civil rights cases of 1883, where the Supreme Court spoke about dual citizenship. In their interpretation, they're saying the 14th Amendment says that the state cannot deprive you of your rights, but an individual in the state can deprive you of your rights because you have rights.

Dr. Lester Brooks: National, national citizenship. Yes, state citizenship. But the 14th Amendment only covers you as far as the nation. And it says the state can't do these things to you, but an individual in the state can. So certainly the owner of the inn can say you're not welcome. So there were these obstacles that still lingered, even though there were these attempts to bring about a more perfect union.

Dr. Lester Brooks: And so in that reconstruction period, there was a tremendous fight. There were boycotts. There were race riots and there were civil rights acts. And this attempt to bring about a more perfect union. And largely, historians say it by the end of reconstruct in most of them were failures. And so we're going to have to sort of repeat some of these things 9000 years later.

Dr. Donna Phillips: And so going into the 20th century, what was the ongoing landscape for civil rights?

Dr. Lester Brooks: Some historians say this is a low point. And the reason they point out this is because of lynching. Latter part of the 19th century, early part of the 20th century, there were hundreds and hundreds of lynchings. And one individual who focused on that was a woman by the name of Ida B Wells-Barnett, and Ida B. Wells-Barnett was a very courageous individual.

Dr. Lester Brooks: She owned newspapers. She was a newspaper editor, and she fought against lynching. She wrote pamphlets against lynching. She wrote newspaper articles against lynching. She tried to mobilize people. She appealed to the presidents and leaders to pass legislation against lynching. And she tried to investigate why lynchings were occurring. And she found out. One of the reasons was economic competition that when Blacks established economic businesses and concerts, if they were in competition with Whites, one way to defeat them is to lynch them.

Dr. Lester Brooks: So lynching was one of the more horrendous activities at that turn of the century. And Ida B. Wells-Barnett was one of the individuals who fought against that. Also, the beginning of the 20th century, we have the NAACP, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, and this was an organization with civil rights as its focus. And one of the key individuals there was W.E.B. Dubois.

Dr. Lester Brooks: As a matter of fact, he was the only Black person in a leadership position in the NAACP. And so we'll see that throughout the 20th century, the ACP took a lead in bringing about lawsuits because one of their key things was to establish legal precedents, bring about civil rights through a court cases. And that was one of the most important things that they were able to accomplish throughout the 20th century.

Dr. Lester Brooks: We'll see time and time again going to court, petitioning courts to try and bring about change. So at that turn of the century, well, the struggle is continuing. Still, the ideals of the Declaration of Independence are there the words of the Constitution to make a more perfect union. They're there. And so we see it in the early part of that 20th century, even though it was a very intense period, because we're in the middle of segregation, 1896, we get the Plessy v. Ferguson case that established a separate but equal doctrine that it was okay to have separate theaters, separate water fountains, separate everything as long as facilities were equal, even though in practice facilities were unequal, you could have separate railroad cars. And so this was the beginning of the 20th century segregation. And so the fight is going to be to try and bring down segregation, to open up society. And that's what we're going to see time and time again in the 20th century. And the NAACP will be right in the middle of this fight to bring about an end to segregation.

Dr. Donna Phillips: And so going forward, a little bit more than. Can you talk a little bit more about the Brown versus Board of Education decision and its impact on segregation and then civil rights ongoing?

Dr. Lester Brooks: When we look at this, the 14th Amendment, we have to go back to that and that phrase the equal protection of the law. So in the field of education, before we even get to Brown, there were attempts by the ACP to bring about the equal protection of law. For instance, there was the pay with teachers. Black teachers were paid less than White teachers facilities.

Dr. Lester Brooks: Blacks faced realities where funds for Black facilities were lot less than funds for White facilities. And so this idea of fighting to equalize pay, equalize funding for facilities was all part of this move toward the Brown versus Board of Education. There were also a number of cases leading up to that. For instance, there was the Gaines case, Louis Gaines [Lloyd Lionel Gaines] in Missouri in 1938.

Dr. Lester Brooks: He wanted to attend the University of Missouri Law School. The state Supreme Court said that he was not allowed to attend the University of Missouri. But the University of Missouri would have to pay his way to a neighboring states law school. Now, ultimately, he never goes to the University of Missouri Law School, but but the idea that he would have to go out of state and you versus Missouri.

Dr. Lester Brooks: That's what the state Supreme Court said, that they would pay his way. The United States Supreme Court stepped in and said the University of Missouri has to accept him. But again, based on that 14th Amendment, equal protection, the law. There was another case, McLaurin v. Oklahoma, and this is 1950. McLaurin Black student, wanted to attend the University of Oklahoma graduate school.

Dr. Lester Brooks: The University of Oklahoma admits him. However, he has a designated seat in the cafeteria that he has to sit in. He has a designated seat in the library where he has to sit. When he goes to class, he sits outside of the classroom with the door open or there's a shield put up. White students on one side, he's on the other.

Dr. Lester Brooks: The US Supreme Court said, no, you can't have that in schools. Segregation, because that's depriving him of his equal rights to gain a graduate education. The mixing of with the other students. And so there were a number of these cases that lead up to the Brown versus Board of Education. And that Board of Education was the Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas.

Dr. Lester Brooks: And there was a school basically right up the street and the Brown family, the child had to go much further than to attend that school. And so there was a lawsuit. And ultimately, the Supreme Court says that segregation in the field of education is unconstitutional because it deprives those individuals of mixing with others. And so we get this tremendous decision.

Dr. Lester Brooks: However, a year later, in 1955, the Supreme Court says to desegregate with all deliberate speed, which now means what? That can be defined a lot of different ways. So now we begin to see delay tactics to prevent the integration of schools. And there were all sorts of of delay tactics to try and stop the integration of schools. For instance, the there was one school board.

Dr. Lester Brooks: This was in Texas. And the state legislature said that if any school board desegregated their schools before for allowing the people in that district to vote on it, then they were subject to punishment and jail again, trying to delay. In Louisiana, there was one school board that said their investigation showed that what should be done is wait until the aptitude of Blacks reaches the aptitude of Whites.

Dr. Lester Brooks: But that is impossible under the conditions at the time. So we get a number of delay tactics with that decision. But one thing that many of my students didn't understand, they were under the impression that the Brown decision destroyed the Plessy case all together, destroyed segregation. And it didn't. It only destroyed segregation in the field of education. There was still the problem of segregation and transportation, segregation in accommodations.

Dr. Lester Brooks: And so once we get to the field of of transportation, we can turn to the Montgomery bus boycott. And again, usually when we hear about the Montgomery bus boycott, immediately the name Rosa Parks comes to mind. And I always tell my students. Rosa Parks was a pivotal figure, but she also worked with the local NAACP. And so she was not innocent.

Dr. Lester Brooks: She understood the circumstances. She had been working for civil rights before this. She had even been sent to investigate rapes of Black women before this. So she knew exactly what she was doing. Sometimes we only hear Rosa Parks and we hear about Martin Luther King and the Montgomery bus boycott. We don't hear about Jo Ann Robinson, who belonged to the Women's Political Council there in Montgomery, who was pivotal in helping to keep the bus boycott going on a day to day basis.

Dr. Lester Brooks: She was cranking out the leaflets that were sent out to call for a boycott, and she continually helped to mobilize people to support the boycott. And so there were others who were involved in that Montgomery bus boycott other than Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King. Not to take anything away from them. Also in transportation. So here there are literally chipping away at the Plessy v. Ferguson, separate but equal doctrine.

Dr. Lester Brooks: And that Brown chipped away a little bit. Now, the Montgomery bus boycott and transportation, we can also go to the Freedom Rides. The Freedom Rides were organized by the Congress of Racial Equality Corps, which was founded by James Farmer. And this was an absolutely incredible endeavor. This the Congress of Racial Equality, an integrated group. They were going to start in Washington, D.C., and they were going to ride the Greyhound bus from Washington, D.C. to New Orleans, Louisiana.

Dr. Lester Brooks: Now, this is an integrated group. So the Black members would go into the White section of a terminal, though the White members would go into the Black section. And so what they were trying to prove that desegregation had taken place before they got on the bus, they were writing down next of kin in case something happened. So, you know, just just that the courage to continue on.

Dr. Lester Brooks: And as individuals, many people know that eventually they ran into all sorts of problems. They were beaten at different spots. They were hit by clubs and chains. The bus was burned and in one spot. So just a tremendous effort. It got to one point. The farmer had to call off the the trip. And so, again, this was an attempt to bring about the end of segregation in the field of transportation.

Dr. Lester Brooks: So there was that fight going on. There were other groups. And I want to mention the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, led by many ministers. Martin Luther King is perhaps the most famous individual connected with the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. But also for a brief period, there was a woman by the name of Ella Baker, who also served as an officer in SLC.

Dr. Lester Brooks: Ella Baker many times gets overlooked. Tremendous individual who fought for civil rights for decades. She had more experience being king at organizing and fighting for civil rights, and she was going to be heard. She did not bite her tongue. She was going to be heard. But what's amazing is there was the sit in movement in the early 1960s where college students were sitting in in various locales.

Dr. Lester Brooks: Now, it started in one of the places it started was in Greensboro, North Carolina. And students went to a local restaurant and sat in. And then you get sit ins throughout the South. Ella Baker said they should organize and she helped them to bring about an organizational meeting in Raleigh, North Carolina. And out of that comes the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee.

Dr. Lester Brooks: And so Ella Baker was instrumental in that. And she told the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, commonly referred to as "SNICK," that they should be independent from the SCLC. And these were young students. Some of the most courageous Americans you will ever read about are these young people of core and snick that engaged in the sit ins because there were rules.

Dr. Lester Brooks: When you went to sit in at a restaurant, you could not respond to the treatment. So if you're sitting at the counter and someone pours a Coke over your head, you can't respond. If someone pours ketchup over you, you can't respond if someone takes a cigarette and burns you in the back. You can't respond if you're punched. You can't respond.

Dr. Lester Brooks: So there were these rules that were established and the young people that were engaged in this were absolutely amazing. And you can't say enough about some of these individuals who were involved in that in the movement, the sit in movement, the Freedom Rides, going into voting. If we if we talk about well, let me mention accommodations, because I said we talked about the education destroying policy in the field of education, destroying policy in the field of transportation.

Dr. Lester Brooks: But also there was a fight to destroy policy in the field of accommodations. And one place to look to see this fight was in the Birmingham campaign. And certainly there is Martin Luther King in the middle of the Birmingham campaign. And one of the most important documents of the modern civil rights struggle was his letter from a Birmingham jail.

Dr. Lester Brooks: That is a must read because he explains many times people think that Martin Luther King believed in turning the other cheek. He did not. He believed in nonviolent direct action. He said, You go into a community and you nonviolently stir things up. You cause a commotion and force that community to address the conditions, the unbearable conditions, the oppressive conditions.

Dr. Lester Brooks: So it's not turning the other cheek. It's nonviolently forcing the community to deal with the oppressive conditions. And that's what he was doing in Birmingham. But he wasn't the only one. There was a man by the name of Fred Shuttlesworth was already in Birmingham. And Fred Shuttlesworth is again another one of these courageous civil rights fighters. At one point, he wanted to integrate the local high school with his daughter and his he his wife and his daughter drove up to the school and they were attacked by a mob.

Dr. Lester Brooks: The mob is beating him up. His wife gets out the car to try and help. He will get stabbed. The daughter will try and get out. The door will be slammed against her leg and broken. So Fred Shuttlesworth is just so courageous because he continually fought and fought and fought and the violence that, you know, Birmingham was nicknamed Bombingham because so many bombs went off in the community.

Dr. Lester Brooks: King was threatened at Montgomery with bombs. And at one point, Coretta Scott King was sitting in the house talking to a friend, and they heard a thump and they ran to the other end of the house and the bomb exploded, damaging right where they had been sitting. So these were sincere threats. These were really some serious times. And people were afraid.

Dr. Lester Brooks: One of the phrases in that song, "We Shall Overcome," is "we are not afraid" because people had to convince themselves that they had to stand up against the violence that was being thrown in their way. And people gathered some support in that way. They had meetings where people could stand up and give testimony. They had rallies where you could see people in the community coming forward.

Dr. Lester Brooks: And that gave you some support and the courage necessary to carry on the fight. And so in accommodations, partly the Birmingham campaign helped to bring about the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which opened up accommodations. But think about this. We can go all the way back to 1875. In 1875, there was a Civil Rights Act that essentially said the same thing that the 1964 Civil Rights Act said open accommodations.

Dr. Lester Brooks: And so we see a 90-year period and the struggle again, is continuing. We can also look at voting voting rights, because as we've seen, the 15th Amendment allow for loopholes to keep Blacks voting. So there was, again, this attempt to bring about the expansion of voting rights. And one campaign that dealt with that was the Selma campaign.

Dr. Lester Brooks: This campaign, the idea was to march from Montgomery, from Selma to Montgomery, and that was about a 50-mile march. And that's what they were going to do to protest. And they would march out a few miles and then some would go back to Selma to spend the night. And then they'd march a few more the next day.

Dr. Lester Brooks: Some would stay right where they ended the march, but this Selma campaign. And just to show you the intensity here, people died. And throughout this entire movement. But for example, there was Jimmy Lee Jackson, a young man who a police officer was harassing his mother. He stepped in to protect her and was shot and killed by a White male by the name of Reverend James Reeb, walking down the street.

Dr. Lester Brooks: And there were several individuals that came toward him and one swung a two by four, hitting him in the head, killed James Reeb, Viola Liuzzo, a White housewife from Detroit who drove down to participate in the Selma campaign. Now, she was shuttling the marchers back and forth from Selma to the place where they had stopped. And one night she had a young man in the car in the front seat while a car full of Klansmen drove up, shot into the car, killing all of these.

Dr. Lester Brooks: How now they get out, look in the car and they see her blood was all over the other person as well. And he played dead. So they thought they killed him and got back in the. And the reason we know what happened is one of the members in the car of Klansmen was an FBI informant. So here is this Detroit housewife who believed in civil rights and loses her life.

Dr. Lester Brooks: So this was the Selma campaign, but this also helped to bring about the Voting Rights Act of 1965. And certainly there were other protests going on to bring about voting rights, the expansion of voting, and to get rid of the literacy tests and any other obstacles. So the Voting Rights Act said that, yeah, there could be an investigation, there could be federal officials that went into to territories or areas or districts where there had been discrimination in, voting rights.

Dr. Lester Brooks: So the story of for civil rights in this country is long, but we can go right back to the Declaration of Independence and the principles presented there and that phrase in the Constitution to make a more perfect union. And we can see it all along the way that people have been struggling to expand the rights. And this is just one of the struggles for Black Americans.

Dr. Lester Brooks: There's also a fight going on for women's rights, for gay rights, for Native American rights, Latino rights. So there is still more room to come to to grow. We still have that path to a more perfect union. And we will continue in this. Frederick Douglass says he has hope for the future.

Dr. Donna Phillips: Yeah, I like how you brought it back around to the words of the Constitution and striving towards more perfect union. Do you what what would you say are the biggest challenges still facing us today?

Dr. Lester Brooks: We still have a percentage of Americans that are not willing to expand the principles of the Declaration of Independence any further. And that's what we have to do. We have to keep expanding the principles of the declaration of. Now, certainly there are individuals who are in power. They're in positions of influence. But also we have to educate the people.

Dr. Lester Brooks: We have to get the right people elected that can bring about the changes. And that's where we are right now, that we have to continue educating individuals. And that's what we're doing here with this civic education, a civic discourse. These are crucial. Placing a greater emphasis on American history, educating the American public so that we can advance further toward a more perfect union.

Dr. Lester Brooks: So certainly we have problems when we talk about all men are created equal. We're not there yet. Things are not equal. And we have to keep moving toward providing more equality in the country and being more inclusive. Because we say we're a democracy, we have to be more inclusive. And one of the reasons we have to be more inclusive is individuals have ideas.

Dr. Lester Brooks: They have answers to some of the questions that are facing us. And we need those answers. We need are people to bring that brainpower and that ingenuity to help us resolve some of the issues that we're still facing. And so when you're inclusive, you are bringing more of those ideas and more of those answers that we need to make a more perfect union.

Dr. Donna Phillips: Thank you so much, Dr. Brooks.

Dr. Lester Brooks: Thank you.

Dr. Donna Phillips: This has been Beyond the Legacy with our focus on civil rights. Thank you for joining us.

Dr. Lester Brooks: Thank you.

Dr. Donna Phillips: I'm really excited to go deeper into our topic of civil rights. And I wonder if you can start off by talking with us about how the decisions of our founders and framers shaped the challenges and battles for civil rights.

Dr. Lester Brooks: We can go straight to the Declaration of Independence because of the principles that were established in that document. Certainly, these were ideals, the revolutionary ideology. All men are created equal. Now, certainly there were flaws, but it puts us on the path to make a more perfect union. And certainly in the revolutionary period, we saw that in the Black community, there were petitions sent to provincial legislatures seeking emancipation.

Dr. Lester Brooks: And so we can find this in Massachusetts. We can find it in Connecticut seeking emancipation later. The idea of segregation will come about. But again, we can go right to the Declaration of Independence. When we talk about that revolutionary period, the Declaration of Independence and its principles sets us on a path to make a more perfect union. There was one individual at the time by the name of Lemuel Haynes, who wrote a pamphlet called Liberty Extended.

Dr. Lester Brooks: And he essentially was saying that the the Declaration of Independence should be extended to incorporate the Black community and to incorporate others. And so we get these ideas that were generated in the revolutionary period. The British offered freedom to those Blacks that would come and support the British cause. So that was one option because the Black community was seeking liberty.

Dr. Lester Brooks: They were seeking freedom. Certainly the Patriot Cause ultimately open its enlistments to Blacks as well to fight. So this idea of liberty was embedded in the Black community and freedom. And if we look at that period, those principles were crucial and they were sort of like a bedrock for people in this country. Liberty, freedom and certainly the words in the Constitution to make a more perfect union was something that people strove to bring about.

Dr. Donna Phillips: And so our country was founded very imperfectly with this goal of a more perfect union. And these principles articulated in the declaration and kind of codified by the Constitution. But they didn't apply to everyone.

Dr. Lester Brooks: Absolutely. If we look at the Declaration of Independence, certainly women weren't included. Blacks included. Native Americans weren't included. But the words themselves left an opening. And with that opening up, individuals began to seek to extend those principles to a wider audience. And that's been the struggle in this country to extend the principles of the declaration to a wider audience here in America and to incorporate all Americans.

Dr. Donna Phillips: And so if we jump forward a little bit and we look at Frederick Douglass and his invitation to speak at the Fourth of July celebration. What did he have to say about our civil rights journey?

Dr. Lester Brooks: Frederick Douglass, one of the most courageous of the abolitionists. So here, by the antebellum period, the early 1800s, we get the abolitionist movement. And Frederick Douglass was one of the key individuals there. And his speech, what to the slave is the Fourth of July celebrates that the ideas of the Declaration of Independence. And he continually talks about the Declaration of Independence and those principles.

Dr. Lester Brooks: I'd like to quote Frederick Douglass from that speech, because I think it's very timely. Douglass says this. "What have I or those I represent to do with your national independence are the great principles of the Declaration of Independence extended to us. Your high independence only reveals the immeasurable distance between us. The blessings in which you rejoice are not enjoyed in common."

Dr. Lester Brooks: "The rich inheritance of justice, liberty, profits, prosperity and independence bequeathed by your fathers is shared by you, not by me. The Fourth of July is yours, not mine." So these are powerful words from Frederick Douglass, who is recognizing the contradiction in the declaration of Independence. Yet he holds out hope. He's saying later in this speech that he still has hope for the future of the country, that things will work out.

Dr. Lester Brooks: So he, too, saw that this was a struggle, that this was an evolutionary process, and that there is this slowly chipping away at the institution of slavery, that the principles of the Declaration of Independence would in the future be extended to all. In addition to Frederick Douglass, there were others in the abolitionist movement that were fighting for civil rights.

Dr. Lester Brooks: There was a White individual by the name of William Lloyd Garrison, who also was very outspoken. And one of the words that one of the phrases of Garrison I really liked, he said, you can't. So the argument was, should slavery be abolished immediately or gradually? And there was a discussion at that time about immediate ism or gradualism. And William Lloyd Garrison, his argument was, you can't tell a woman whose house is on fire that you will gradually put out the fire.

Dr. Lester Brooks: And that really captures a very important aspect here of abolitionists and slavery. He was saying we should immediately begin to emancipate the slaves, abolish the institution of slavery. And I think his input is that he moved the the abolitionist movement along and propelled it further down the cause of immediate abolition. There were others, Sojourner Truth, also, who was protesting for abolishing the institution of slavery, as well as for extending women's rights.

Dr. Lester Brooks: So there were a number of abolitionists who were attempting to bring about the fulfillment of the principles of the Declaration of Independence. And we can't forget those individuals because they had a huge uphill climb to try and bring about the end of the institution of slavery.

Dr. Donna Phillips: And and so getting to the other side of the Civil War and then we have the Reconstruction Amendments. And how did they move the needle in terms of civil rights?

Dr. Lester Brooks: The Reconstruction era was a profound period in American history, in particular for the freedmen. The 13th Amendment abolished the institution of slavery. This is major. This is changing the status of Black Americans forever. It's abolishing the institution of slavery. Of course there is. That question was dropping the shackles? Was removing the shackles? Was that enough? Was there more?

Dr. Lester Brooks: Do you have to put flesh on this? What else is there, then? Just dropping the shackles. And so we begin to see a civil rights era. 1866. There was a Civil Rights Act, and this was the first attempt to try and put some flesh on that 13th Amendment, a Civil Rights Act. And usually we don't think about Civil Rights Act, Civil Rights Act in that period of reconstruction.

Dr. Lester Brooks: But the Civil Rights Act of 1866 essentially was saying that the freedmen would be citizens of the United States. And essentially they were trying to nullify what were called the Black codes that were popping up in the southern states that were restrictions placed on the Black community, keeping them without property and without power, without influence. So here we get a Civil Rights Act in 1866.

Dr. Lester Brooks: The 14th Amendment comes about. The 14th Amendment at the time essentially was saying that Blacks were citizens of the United States. So, again, putting more teeth to that Civil Rights Act of 1866. The 14th Amendment talks about citizenship for the freedmen. It also talks about the equal protection of the laws. And I think that phrase is going to be extremely important in the 20th century because the 14th Amendment will be used time and time again to extend the principles that were presented in the Declaration of Independence and the words of the Constitution to make a more perfect union.

Dr. Lester Brooks: The 15th Amendment. The Voting Rights Amendment. Now, it was carefully crafted at that time. Carefully worded because it left loopholes, for instance, in in crafting the wording, no one wanted women to vote in that time period. So it was crafted to continue to keep women from voting. It was also it allowed loopholes to keep Blacks from voting. So here we get the loophole tax.

Dr. Lester Brooks: If you want to vote, you have to pay. Let's say you have to pay a dollar. Well, majority of Blacks then have the overwhelming majority of Blacks didn't have a dollar, and so they would not be allowed to vote. And if I'm the White registrar, even if they have the money, I won't let them vote. Poll taxes. There were also literacy tests.

Dr. Lester Brooks: If, again, I'm the White registrar and a Black person wants to vote, I'll say, Here's a paragraph of the US Constitution. Read that paragraph for me. Now, approximately 90% of the freedmen could not read coming out of slavery. So again, the idea of a literacy test is going to exclude many in the Black population. But again, if I'm the White registrar and I do fine, one of the percentage to a Black person that can read.

Dr. Lester Brooks: Now my question will be read that paragraph and explain it to my satisfaction, which they will never be able to to do. So that was another way to keep Blacks from voting. A third method to keep Blacks from voting was the grandfather clause and extraordinary tactic. And we've seen political tricks throughout the history of politics in this country.

Dr. Lester Brooks: This is an extraordinary one where I can say to a Black person, I will let you vote. If your grandfather could vote in the election of 1860. Well, certainly no grandfather, no Black person could vote in the election of 1860. So I'm not in violation of the 15th Amendment because I'm not using race as a means of keeping that person from voting.

Dr. Lester Brooks: Because, again, the way that the 15th Amendment is crafted, it says race wins are not keeping individuals from voting based on their race. I'm saying because your grandfather couldn't vote. You're not allowed to vote. Now there will be another about another there'll be another case, a race, us versus race. I believe it is where the court will say that the 15th Amendment doesn't confer.

Dr. Lester Brooks: It just says why you can't keep people from voting. It doesn't say that you have to actually vote. So there were a lot of ways to play with that. The loophole in the 15th Amendment to keep individuals from voting. The grandfather clause will last into the 20th century. Literacy test will last into the 1960s, where in the 1960s, I might say to a person who wants to vote here, read this paragraph of the state constitution or copy this paragraph or copy the entire state constitution.

Dr. Lester Brooks: So the literacy tests are going to last into the 1960s, so that fine, it's going to last a very long time. With regard to the 15th Amendment and voting. So when we look at the reconstruction amendments, after they're called the 13th, 14th and 15th, they move the needle tremendously. They open the door. Now, certainly there were drawbacks. There were still obstacles to overcome.

Dr. Lester Brooks: For example, 1875, we get a Civil Rights Act again. Now 1866, we have one 1875, a civil Rights act essentially said that INS, hotels, theaters, accommodations should be open to Blacks. Well, there are a number of cases, such as the civil rights cases of 1883, where the Supreme Court spoke about dual citizenship. In their interpretation, they're saying the 14th Amendment says that the state cannot deprive you of your rights, but an individual in the state can deprive you of your rights because you have rights.

Dr. Lester Brooks: National, national citizenship. Yes, state citizenship. But the 14th Amendment only covers you as far as the nation. And it says the state can't do these things to you, but an individual in the state can. So certainly the owner of the inn can say you're not welcome. So there were these obstacles that still lingered, even though there were these attempts to bring about a more perfect union.

Dr. Lester Brooks: And so in that reconstruction period, there was a tremendous fight. There were boycotts. There were race riots and there were civil rights acts. And this attempt to bring about a more perfect union. And largely, historians say it by the end of reconstruct in most of them were failures. And so we're going to have to sort of repeat some of these things 9000 years later.

Dr. Donna Phillips: And so going into the 20th century, what was the ongoing landscape for civil rights?

Dr. Lester Brooks: Some historians say this is a low point. And the reason they point out this is because of lynching. Latter part of the 19th century, early part of the 20th century, there were hundreds and hundreds of lynchings. And one individual who focused on that was a woman by the name of Ida B Wells-Barnett, and Ida B. Wells-Barnett was a very courageous individual.

Dr. Lester Brooks: She owned newspapers. She was a newspaper editor, and she fought against lynching. She wrote pamphlets against lynching. She wrote newspaper articles against lynching. She tried to mobilize people. She appealed to the presidents and leaders to pass legislation against lynching. And she tried to investigate why lynchings were occurring. And she found out. One of the reasons was economic competition that when Blacks established economic businesses and concerts, if they were in competition with Whites, one way to defeat them is to lynch them.

Dr. Lester Brooks: So lynching was one of the more horrendous activities at that turn of the century. And Ida B. Wells-Barnett was one of the individuals who fought against that. Also, the beginning of the 20th century, we have the NAACP, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, and this was an organization with civil rights as its focus. And one of the key individuals there was W.E.B. Dubois.

Dr. Lester Brooks: As a matter of fact, he was the only Black person in a leadership position in the NAACP. And so we'll see that throughout the 20th century, the ACP took a lead in bringing about lawsuits because one of their key things was to establish legal precedents, bring about civil rights through a court cases. And that was one of the most important things that they were able to accomplish throughout the 20th century.

Dr. Lester Brooks: We'll see time and time again going to court, petitioning courts to try and bring about change. So at that turn of the century, well, the struggle is continuing. Still, the ideals of the Declaration of Independence are there the words of the Constitution to make a more perfect union. They're there. And so we see it in the early part of that 20th century, even though it was a very intense period, because we're in the middle of segregation, 1896, we get the Plessy v. Ferguson case that established a separate but equal doctrine that it was okay to have separate theaters, separate water fountains, separate everything as long as facilities were equal, even though in practice facilities were unequal, you could have separate railroad cars. And so this was the beginning of the 20th century segregation. And so the fight is going to be to try and bring down segregation, to open up society. And that's what we're going to see time and time again in the 20th century. And the NAACP will be right in the middle of this fight to bring about an end to segregation.

Dr. Donna Phillips: And so going forward, a little bit more than. Can you talk a little bit more about the Brown versus Board of Education decision and its impact on segregation and then civil rights ongoing?

Dr. Lester Brooks: When we look at this, the 14th Amendment, we have to go back to that and that phrase the equal protection of the law. So in the field of education, before we even get to Brown, there were attempts by the ACP to bring about the equal protection of law. For instance, there was the pay with teachers. Black teachers were paid less than White teachers facilities.

Dr. Lester Brooks: Blacks faced realities where funds for Black facilities were lot less than funds for White facilities. And so this idea of fighting to equalize pay, equalize funding for facilities was all part of this move toward the Brown versus Board of Education. There were also a number of cases leading up to that. For instance, there was the Gaines case, Louis Gaines [Lloyd Lionel Gaines] in Missouri in 1938.

Dr. Lester Brooks: He wanted to attend the University of Missouri Law School. The state Supreme Court said that he was not allowed to attend the University of Missouri. But the University of Missouri would have to pay his way to a neighboring states law school. Now, ultimately, he never goes to the University of Missouri Law School, but but the idea that he would have to go out of state and you versus Missouri.

Dr. Lester Brooks: That's what the state Supreme Court said, that they would pay his way. The United States Supreme Court stepped in and said the University of Missouri has to accept him. But again, based on that 14th Amendment, equal protection, the law. There was another case, McLaurin v. Oklahoma, and this is 1950. McLaurin Black student, wanted to attend the University of Oklahoma graduate school.

Dr. Lester Brooks: The University of Oklahoma admits him. However, he has a designated seat in the cafeteria that he has to sit in. He has a designated seat in the library where he has to sit. When he goes to class, he sits outside of the classroom with the door open or there's a shield put up. White students on one side, he's on the other.

Dr. Lester Brooks: The US Supreme Court said, no, you can't have that in schools. Segregation, because that's depriving him of his equal rights to gain a graduate education. The mixing of with the other students. And so there were a number of these cases that lead up to the Brown versus Board of Education. And that Board of Education was the Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas.

Dr. Lester Brooks: And there was a school basically right up the street and the Brown family, the child had to go much further than to attend that school. And so there was a lawsuit. And ultimately, the Supreme Court says that segregation in the field of education is unconstitutional because it deprives those individuals of mixing with others. And so we get this tremendous decision.

Dr. Lester Brooks: However, a year later, in 1955, the Supreme Court says to desegregate with all deliberate speed, which now means what? That can be defined a lot of different ways. So now we begin to see delay tactics to prevent the integration of schools. And there were all sorts of of delay tactics to try and stop the integration of schools. For instance, the there was one school board.

Dr. Lester Brooks: This was in Texas. And the state legislature said that if any school board desegregated their schools before for allowing the people in that district to vote on it, then they were subject to punishment and jail again, trying to delay. In Louisiana, there was one school board that said their investigation showed that what should be done is wait until the aptitude of Blacks reaches the aptitude of Whites.

Dr. Lester Brooks: But that is impossible under the conditions at the time. So we get a number of delay tactics with that decision. But one thing that many of my students didn't understand, they were under the impression that the Brown decision destroyed the Plessy case all together, destroyed segregation. And it didn't. It only destroyed segregation in the field of education. There was still the problem of segregation and transportation, segregation in accommodations.

Dr. Lester Brooks: And so once we get to the field of of transportation, we can turn to the Montgomery bus boycott. And again, usually when we hear about the Montgomery bus boycott, immediately the name Rosa Parks comes to mind. And I always tell my students. Rosa Parks was a pivotal figure, but she also worked with the local NAACP. And so she was not innocent.

Dr. Lester Brooks: She understood the circumstances. She had been working for civil rights before this. She had even been sent to investigate rapes of Black women before this. So she knew exactly what she was doing. Sometimes we only hear Rosa Parks and we hear about Martin Luther King and the Montgomery bus boycott. We don't hear about Jo Ann Robinson, who belonged to the Women's Political Council there in Montgomery, who was pivotal in helping to keep the bus boycott going on a day to day basis.

Dr. Lester Brooks: She was cranking out the leaflets that were sent out to call for a boycott, and she continually helped to mobilize people to support the boycott. And so there were others who were involved in that Montgomery bus boycott other than Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King. Not to take anything away from them. Also in transportation. So here there are literally chipping away at the Plessy v. Ferguson, separate but equal doctrine.

Dr. Lester Brooks: And that Brown chipped away a little bit. Now, the Montgomery bus boycott and transportation, we can also go to the Freedom Rides. The Freedom Rides were organized by the Congress of Racial Equality Corps, which was founded by James Farmer. And this was an absolutely incredible endeavor. This the Congress of Racial Equality, an integrated group. They were going to start in Washington, D.C., and they were going to ride the Greyhound bus from Washington, D.C. to New Orleans, Louisiana.

Dr. Lester Brooks: Now, this is an integrated group. So the Black members would go into the White section of a terminal, though the White members would go into the Black section. And so what they were trying to prove that desegregation had taken place before they got on the bus, they were writing down next of kin in case something happened. So, you know, just just that the courage to continue on.

Dr. Lester Brooks: And as individuals, many people know that eventually they ran into all sorts of problems. They were beaten at different spots. They were hit by clubs and chains. The bus was burned and in one spot. So just a tremendous effort. It got to one point. The farmer had to call off the the trip. And so, again, this was an attempt to bring about the end of segregation in the field of transportation.

Dr. Lester Brooks: So there was that fight going on. There were other groups. And I want to mention the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, led by many ministers. Martin Luther King is perhaps the most famous individual connected with the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. But also for a brief period, there was a woman by the name of Ella Baker, who also served as an officer in SLC.

Dr. Lester Brooks: Ella Baker many times gets overlooked. Tremendous individual who fought for civil rights for decades. She had more experience being king at organizing and fighting for civil rights, and she was going to be heard. She did not bite her tongue. She was going to be heard. But what's amazing is there was the sit in movement in the early 1960s where college students were sitting in in various locales.

Dr. Lester Brooks: Now, it started in one of the places it started was in Greensboro, North Carolina. And students went to a local restaurant and sat in. And then you get sit ins throughout the South. Ella Baker said they should organize and she helped them to bring about an organizational meeting in Raleigh, North Carolina. And out of that comes the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee.

Dr. Lester Brooks: And so Ella Baker was instrumental in that. And she told the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, commonly referred to as "SNICK," that they should be independent from the SCLC. And these were young students. Some of the most courageous Americans you will ever read about are these young people of core and snick that engaged in the sit ins because there were rules.

Dr. Lester Brooks: When you went to sit in at a restaurant, you could not respond to the treatment. So if you're sitting at the counter and someone pours a Coke over your head, you can't respond. If someone pours ketchup over you, you can't respond if someone takes a cigarette and burns you in the back. You can't respond if you're punched. You can't respond.

Dr. Lester Brooks: So there were these rules that were established and the young people that were engaged in this were absolutely amazing. And you can't say enough about some of these individuals who were involved in that in the movement, the sit in movement, the Freedom Rides, going into voting. If we if we talk about well, let me mention accommodations, because I said we talked about the education destroying policy in the field of education, destroying policy in the field of transportation.

Dr. Lester Brooks: But also there was a fight to destroy policy in the field of accommodations. And one place to look to see this fight was in the Birmingham campaign. And certainly there is Martin Luther King in the middle of the Birmingham campaign. And one of the most important documents of the modern civil rights struggle was his letter from a Birmingham jail.

Dr. Lester Brooks: That is a must read because he explains many times people think that Martin Luther King believed in turning the other cheek. He did not. He believed in nonviolent direct action. He said, You go into a community and you nonviolently stir things up. You cause a commotion and force that community to address the conditions, the unbearable conditions, the oppressive conditions.

Dr. Lester Brooks: So it's not turning the other cheek. It's nonviolently forcing the community to deal with the oppressive conditions. And that's what he was doing in Birmingham. But he wasn't the only one. There was a man by the name of Fred Shuttlesworth was already in Birmingham. And Fred Shuttlesworth is again another one of these courageous civil rights fighters. At one point, he wanted to integrate the local high school with his daughter and his he his wife and his daughter drove up to the school and they were attacked by a mob.

Dr. Lester Brooks: The mob is beating him up. His wife gets out the car to try and help. He will get stabbed. The daughter will try and get out. The door will be slammed against her leg and broken. So Fred Shuttlesworth is just so courageous because he continually fought and fought and fought and the violence that, you know, Birmingham was nicknamed Bombingham because so many bombs went off in the community.

Dr. Lester Brooks: King was threatened at Montgomery with bombs. And at one point, Coretta Scott King was sitting in the house talking to a friend, and they heard a thump and they ran to the other end of the house and the bomb exploded, damaging right where they had been sitting. So these were sincere threats. These were really some serious times. And people were afraid.

Dr. Lester Brooks: One of the phrases in that song, "We Shall Overcome," is "we are not afraid" because people had to convince themselves that they had to stand up against the violence that was being thrown in their way. And people gathered some support in that way. They had meetings where people could stand up and give testimony. They had rallies where you could see people in the community coming forward.

Dr. Lester Brooks: And that gave you some support and the courage necessary to carry on the fight. And so in accommodations, partly the Birmingham campaign helped to bring about the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which opened up accommodations. But think about this. We can go all the way back to 1875. In 1875, there was a Civil Rights Act that essentially said the same thing that the 1964 Civil Rights Act said open accommodations.

Dr. Lester Brooks: And so we see a 90-year period and the struggle again, is continuing. We can also look at voting voting rights, because as we've seen, the 15th Amendment allow for loopholes to keep Blacks voting. So there was, again, this attempt to bring about the expansion of voting rights. And one campaign that dealt with that was the Selma campaign.

Dr. Lester Brooks: This campaign, the idea was to march from Montgomery, from Selma to Montgomery, and that was about a 50-mile march. And that's what they were going to do to protest. And they would march out a few miles and then some would go back to Selma to spend the night. And then they'd march a few more the next day.

Dr. Lester Brooks: Some would stay right where they ended the march, but this Selma campaign. And just to show you the intensity here, people died. And throughout this entire movement. But for example, there was Jimmy Lee Jackson, a young man who a police officer was harassing his mother. He stepped in to protect her and was shot and killed by a White male by the name of Reverend James Reeb, walking down the street.

Dr. Lester Brooks: And there were several individuals that came toward him and one swung a two by four, hitting him in the head, killed James Reeb, Viola Liuzzo, a White housewife from Detroit who drove down to participate in the Selma campaign. Now, she was shuttling the marchers back and forth from Selma to the place where they had stopped. And one night she had a young man in the car in the front seat while a car full of Klansmen drove up, shot into the car, killing all of these.

Dr. Lester Brooks: How now they get out, look in the car and they see her blood was all over the other person as well. And he played dead. So they thought they killed him and got back in the. And the reason we know what happened is one of the members in the car of Klansmen was an FBI informant. So here is this Detroit housewife who believed in civil rights and loses her life.

Dr. Lester Brooks: So this was the Selma campaign, but this also helped to bring about the Voting Rights Act of 1965. And certainly there were other protests going on to bring about voting rights, the expansion of voting, and to get rid of the literacy tests and any other obstacles. So the Voting Rights Act said that, yeah, there could be an investigation, there could be federal officials that went into to territories or areas or districts where there had been discrimination in, voting rights.

Dr. Lester Brooks: So the story of for civil rights in this country is long, but we can go right back to the Declaration of Independence and the principles presented there and that phrase in the Constitution to make a more perfect union. And we can see it all along the way that people have been struggling to expand the rights. And this is just one of the struggles for Black Americans.

Dr. Lester Brooks: There's also a fight going on for women's rights, for gay rights, for Native American rights, Latino rights. So there is still more room to come to to grow. We still have that path to a more perfect union. And we will continue in this. Frederick Douglass says he has hope for the future.

Dr. Donna Phillips: Yeah, I like how you brought it back around to the words of the Constitution and striving towards more perfect union. Do you what what would you say are the biggest challenges still facing us today?

Dr. Lester Brooks: We still have a percentage of Americans that are not willing to expand the principles of the Declaration of Independence any further. And that's what we have to do. We have to keep expanding the principles of the declaration of. Now, certainly there are individuals who are in power. They're in positions of influence. But also we have to educate the people.

Dr. Lester Brooks: We have to get the right people elected that can bring about the changes. And that's where we are right now, that we have to continue educating individuals. And that's what we're doing here with this civic education, a civic discourse. These are crucial. Placing a greater emphasis on American history, educating the American public so that we can advance further toward a more perfect union.

Dr. Lester Brooks: So certainly we have problems when we talk about all men are created equal. We're not there yet. Things are not equal. And we have to keep moving toward providing more equality in the country and being more inclusive. Because we say we're a democracy, we have to be more inclusive. And one of the reasons we have to be more inclusive is individuals have ideas.

Dr. Lester Brooks: They have answers to some of the questions that are facing us. And we need those answers. We need are people to bring that brainpower and that ingenuity to help us resolve some of the issues that we're still facing. And so when you're inclusive, you are bringing more of those ideas and more of those answers that we need to make a more perfect union.

Dr. Donna Phillips: Thank you so much, Dr. Brooks.

Dr. Lester Brooks: Thank you.

Dr. Donna Phillips: This has been Beyond the Legacy with our focus on civil rights. Thank you for joining us.